SCIENZA E RICERCA

IPCC: Nearly direct correlation between emissions and global warming

“It is unequivocal that human influence has warmed the atmosphere, ocean and land. Widespread and rapid changes in the atmosphere, ocean, cryosphere and biosphere have occurred.” This is the first key point in the latest report published by IPCC (Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change), contained in the Summary directed at Policymakers who will gather in Glasgow in November 2021 for COP26, the United Nations climate conference where individual countries are expected to commit to lasting efforts in the fight against climate change. Europe and the United States aim to achieve climate neutrality by 2050, while China aims for this goal by 2060, although the latter is also planning to increase its coal consumption until 2030 before gradually reducing it.

The document released on August, 9 2021, co-authored by over 200 climate scientists and approved by 195 governments, is part of the Sixth Assessment Report (AR6) on the state of the Earth’s climate. Two more documents are expected in 2022: one will focus on the impacts of climate change on human societies, while the other will suggest the actions and strategies for reducing greenhouse gas emissions that cause global warming.

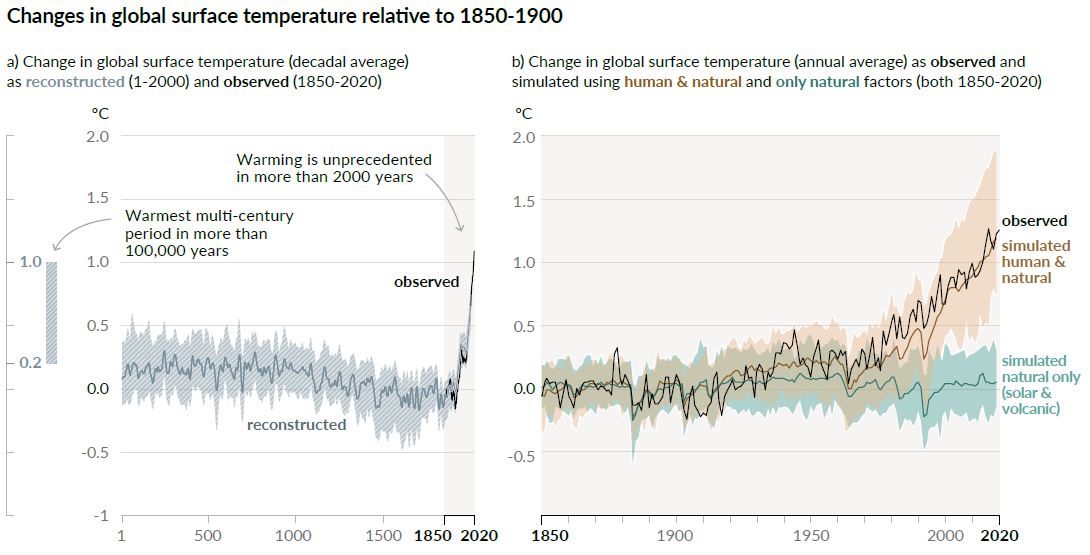

The recently released report represents a synthesis of the most up-to-date scientific knowledge available to understand the climate system. By weaving together evidence from climate in the past, observational data collected in the past decades, insights into climate processes, as well as regional and global simulations, the IPCC report demonstrates with a high level of confidence that global temperatures have increased by approximately 1.1°C compared to the preindustrial era (until the second half of the 19th century). The Earth has not experienced such warm temperatures for 125,000 years.

Findings from the latest #IPCC #ClimateReport:

— IPCC (@IPCC_CH) August 13, 2021

Emissions of greenhouse gases from human activities are responsible for approximately 1.1°C of warming since 1850-1900.

Read more ➡️ https://t.co/uU8bb4zYt9 pic.twitter.com/rAemOMy2tP

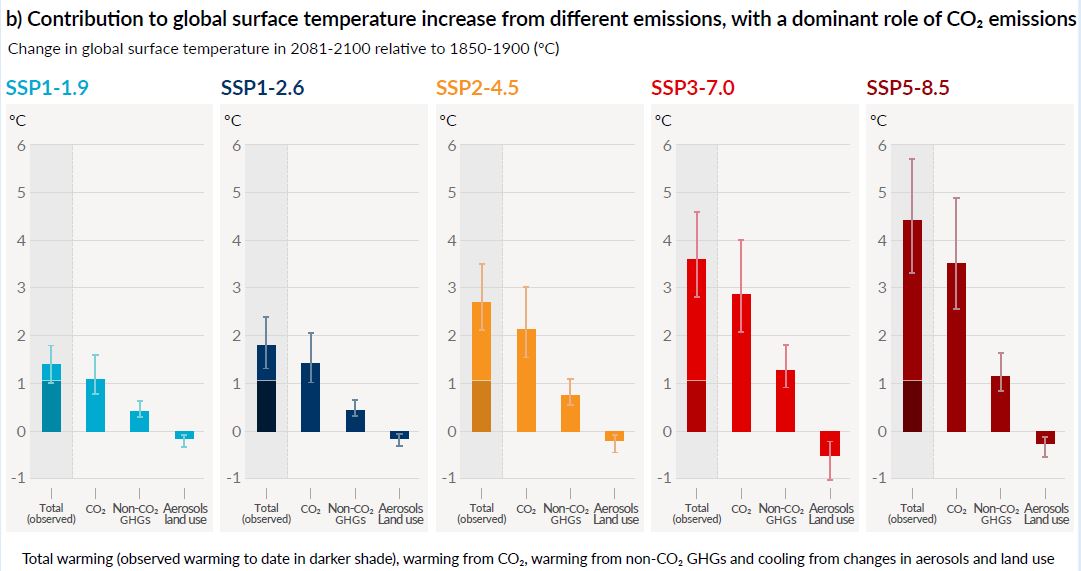

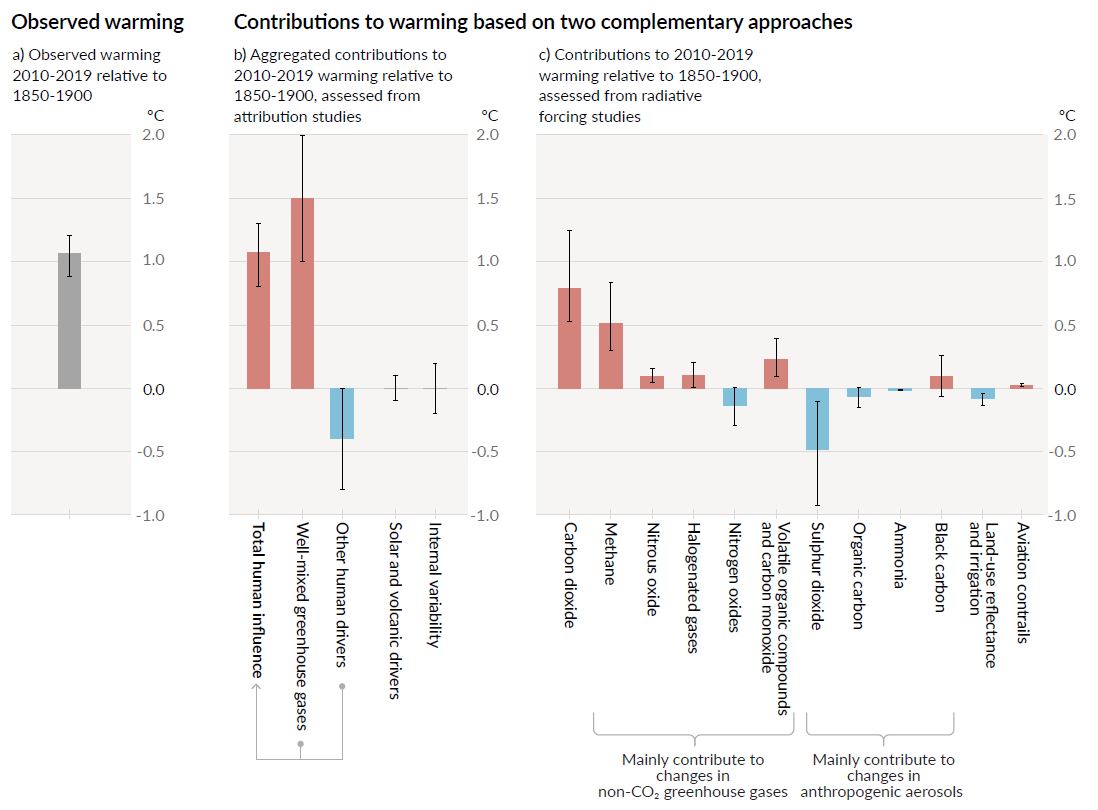

The vast majority of this temperature increase (1.07°C) is attributed to human activities, specifically to the release of greenhouse gases into the atmosphere such as carbon dioxide (CO2), methane (CH4), nitrous oxide (N2O), and other climate-altering substances, most of which come from the energy sector that burns coal, oil, and gas.

Greenhouse gases act like a thermal blanket around the planet. Solar radiation (more precisely, infrared radiation) that enters the atmosphere gets trapped within the bonds of these gas molecules. The higher their concentration in the atmosphere, the higher the Earth’s temperature rises.

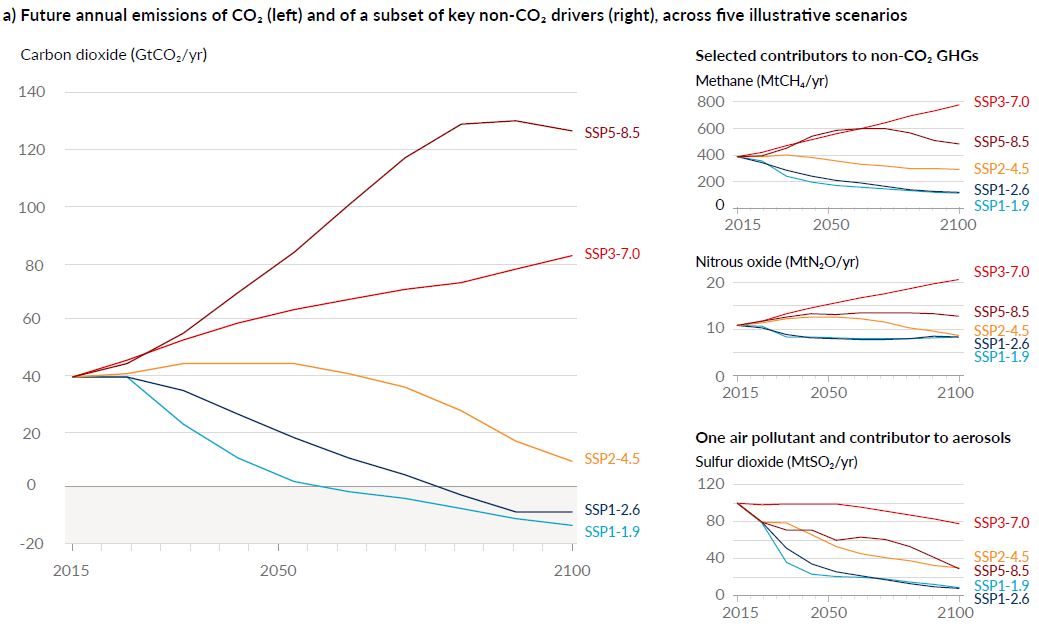

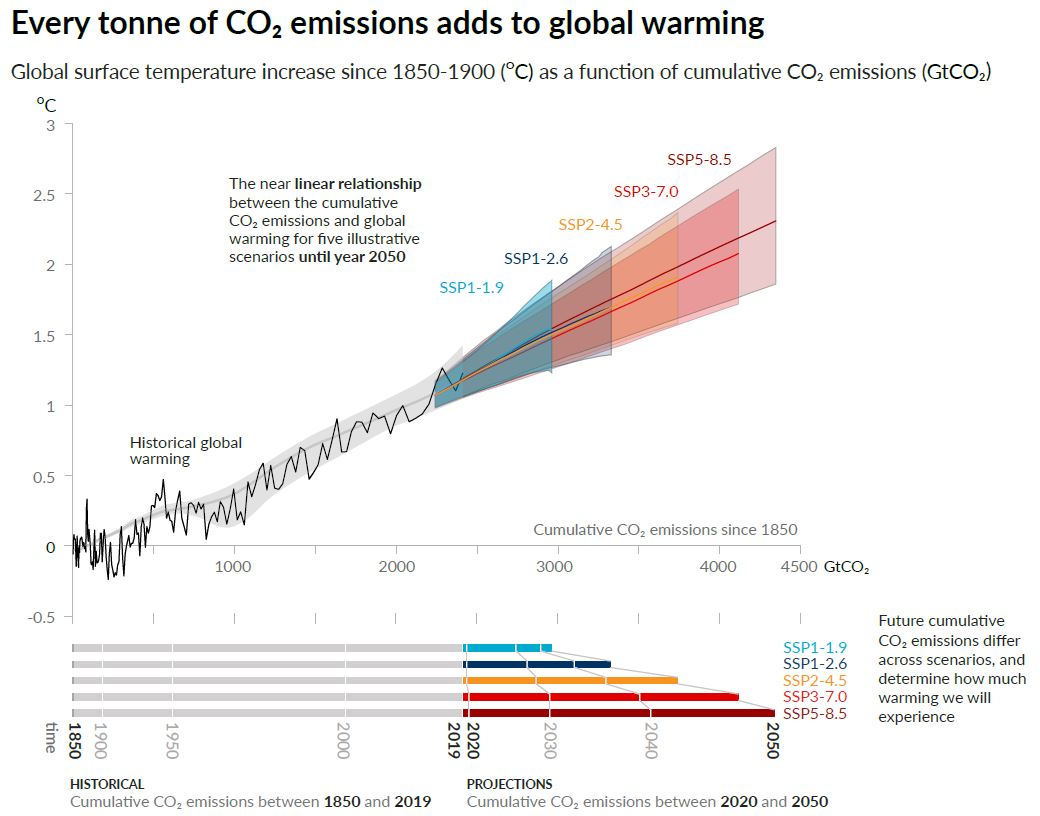

The IPCC sixth assessment report confirms what has been already observed in past reports (the latest report on climate scientific knowledge, AR5, dates back to 2014, and a special report on global warming of 1.5°C was published in 2018-2019): there is a nearly direct correlation (‘near-linear’) between the accumulation of anthropogenic emissions (measured in CO2 equivalent) and global warming, which causes climate change. While in everyday language it may appear as an unremarkable wording, in scientific jargon, a “near-linear correlation” is one of the strongest statements in establishing causal relationships. To every 1,000 billion tonnes (Gt) of CO2 accumulated in the atmosphere corresponds an increase of approximately 0.45°C, and it has been estimated that we have accumulated nearly 2,500 Gt of CO2 from 1850 to the present day.

Emissioni cumulative di anidride carbonica in atmosfera e corrispondente riscaldamento; figura SPM.10, IPCC agosto 2021

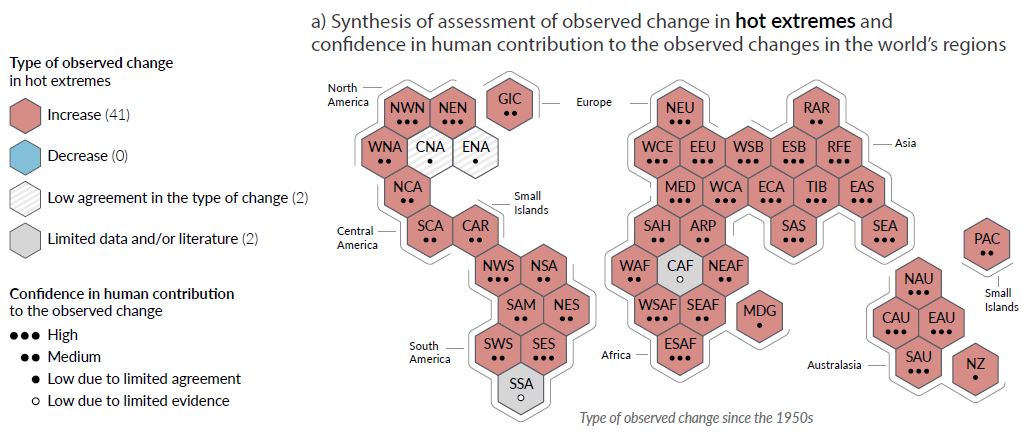

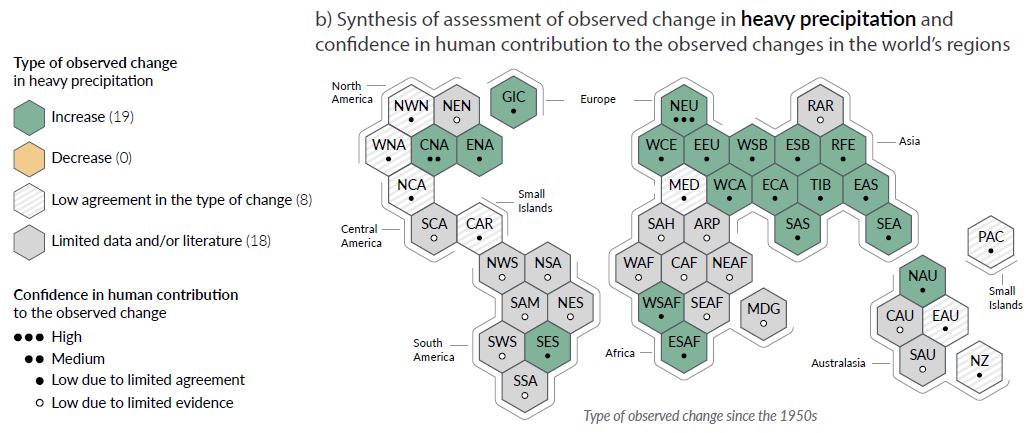

Higher temperatures result in more energy within the climate system. The report states that the consequences will include extreme weather events occurring with greater intensity and frequency than in the past. Heatwaves, heavier precipitation, but also prolonged droughts will strike the planet and its inhabitants more violently.

The report analyses various possible emission scenarios and associated warming. Some long-term effects, such as the melting of glaciers, rising sea levels, ocean acidification, have already crossed the tipping point and are irreversible. However, we can still control the severity of these phenomena by acting swiftly and decisively in this decade to decarbonise the energy sector, freeing our societies from fossil fuels, and investing in renewable energy sources like solar and wind power.

The scenario outlined in the Paris Agreement, signed in 2015 by UN countries aiming to limit global warming to 1.5°C, theoretically remains within reach, as emphasised in the report. Our fate and that of the entire planet are in our hands, albeit for a limited time now: the window of opportunity to act is rapidly closing.

Concentration of greenhouse gases in the atmosphere

Since 1750, concentration of greenhouse gases in the atmosphere have unequivocally increased due to anthropogenic activities. In 2019, carbon dioxide reached 410 ppm (parts per million), the highest value in the past 2 million years; methane stood at 1.8 ppm, and nitrous oxide at 0.3 ppm (their greenhouse effect is tens of times higher than CO2), marking the highest values in the last 800,000 years.

Contributo dei diversi gas al riscaldamento; Figura SPM.2, IPCC agosto 2021

Global temperatures

The planet had not experienced such a warm climate as the present one in 125,000 years. The last four decades have been ever warmer than the preceding ones, and this rate of temperature increase has not been observed in the past 2000 years. The last decade, from 2011 to 2020, averaged a temperature increase of 1.09°C compared to the second half of the 19th century (1850-1900). The mean land surface temperature was even warmer, +1.59°C, while ocean surface temperature rose by 0.88°C.

The report assesses that 1.07°C of the total temperature increase is attributable to anthropogenic activities. Greenhouse gases have triggered a warming estimated to be between 1 and 2°C, while another kind of emissions, aerosols, are responsible for a cooling effect estimated to range from 0 to 0.8°C.

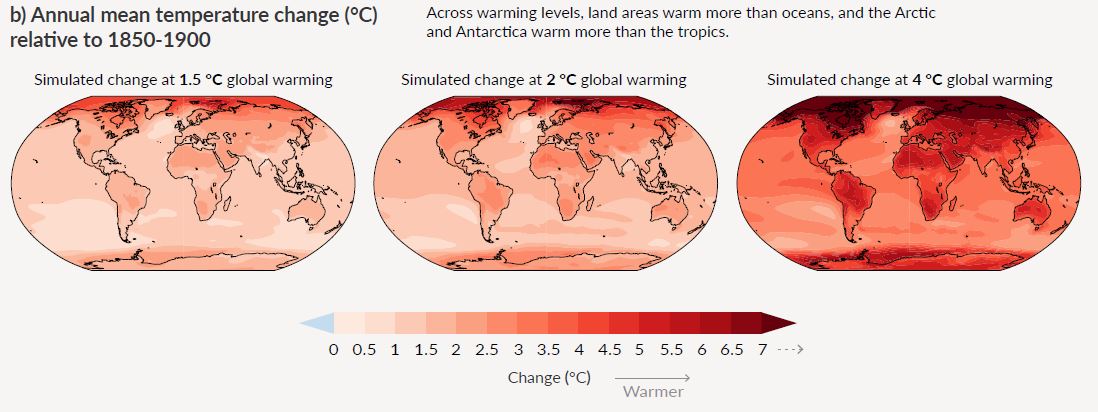

Depending on future emission scenarios, global temperatures will increase by 1-1.8°C by the end of the 21st century if we manage to adhere to the objectives set by the Paris Agreements, which are still within reach, and to achieve zero emissions by 2050. Instead, they will increase by 2.1 to 3.5°C in the intermediate scenario where we continue to emit greenhouse gases at the same pace of present emissions. Finally, in the worst-case scenario, where instead of reducing emissions, we double them, temperatures will rise by at least 3.3°C and at most by 5.7°C. It has been estimated that the last time the planet had experienced mean global temperatures 2,5°C warmer than current levels was over 3 million years ago.

Glaciers

Anthropogenic influence is very likely to be the main reason behind the retreat of ice since the 1990s. In particular, it is responsible for the dramatic reduction of the ice levels in the Arctic from the late 1970s. In the last decade, the ice cover in the Arctic sea reached its historic minimum since 1850, and there has been no comparable ice reduction in the last 1,000 years during summer. Land masses will continue to warm up more rapidly than ocean surfaces, but the Arctic region will suffer the most, warming at a rate two to three times higher than the rest of the planet. It is predicted that, by 2050, the Arctic will be entirely ice-free during the summer months of September.

In the last two decades, the melting of Greenland’s ice cover has also become a reason of concern. In the Northern Hemisphere, spring snow cover has significantly decreased since 1950, and glaciers all over the world tend to retreat, an unprecedented phenomenon in the past 2,000 years.

Only limited evidence is available on the role of anthropogenic activities in causing the ice loss in Antarctica, the report notes.

Regardless of future emissions and warming scenarios, the melting of glaciers, permafrost, Greenland’s ice, Arctic, and Antarctic ice cover, are phenomena that, once initiated, are difficult to stop or reverse. They are destined to continue for decades or centuries.

Oceans

It is virtually certain that the ocean surface (0-700 m) has warmed since 1970 in response to human activities. The pace of such warming is estimated to have not been this high in the past 11,000 years, since the last ice age ended. It is equally certain that CO2 emissions are the primary causa of ocean surface acidification. In several regions, oxygen levels in water have dropped since the mid-20th century. These phenomena are expected to continue independently of any emission reduction we will manage to achieve. The fate of coral reefs, which are biodiversity hotspots in marine ecosystems, seems tragically marked by a grim future.

Storia della temperatura del pianeta, negli ultimi 2000 anni e negli ultimi 170 anni; Figura SPM.1, IPCC agosto 2021

Sea levels

From the beginning of the 20th century to the present day, sea levels have risen by 20 cm at accelerating rates not seen in 3,000 years. The rate of increase was 1.3 mm per year until the 1970s, 1.9 mm per year until 2006, and 3.7 mm per year from 2006 to 2018. During the latter period, the main driver of the rise of sea levels was the melting of glaciers and ice cover on land (such as in Greenland).

Sea levels are also projected to further rise in the coming decades and centuries, regardless of any human mitigation actions. Compared to the 2000s, by the end of the 21st century the additional rise will range between 20 cm and 1 m, depending on global warming scenarios. However, the authors of the report emphasise that the rate of ice melt is hard to predict, and by the end of the century, sea levels could be even higher, possibly by up to 2 m, with significant implications, especially for coastal settlements.

Extreme weather events

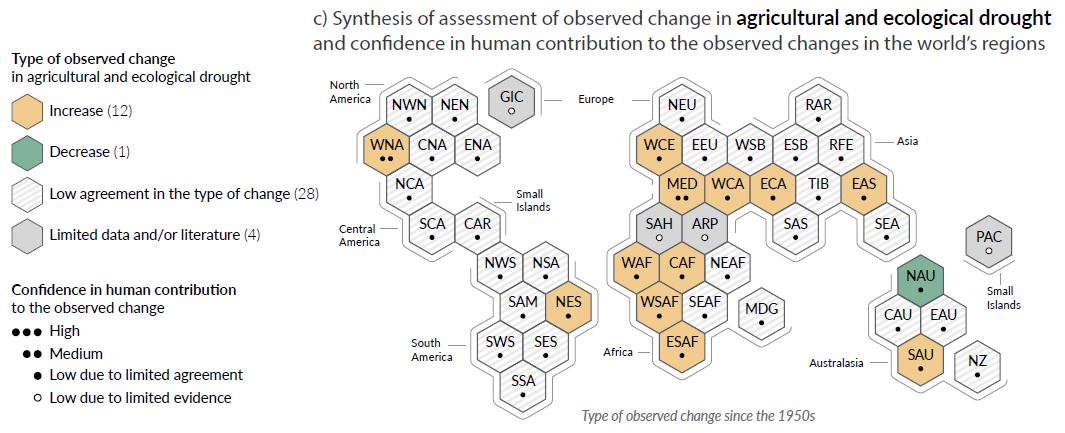

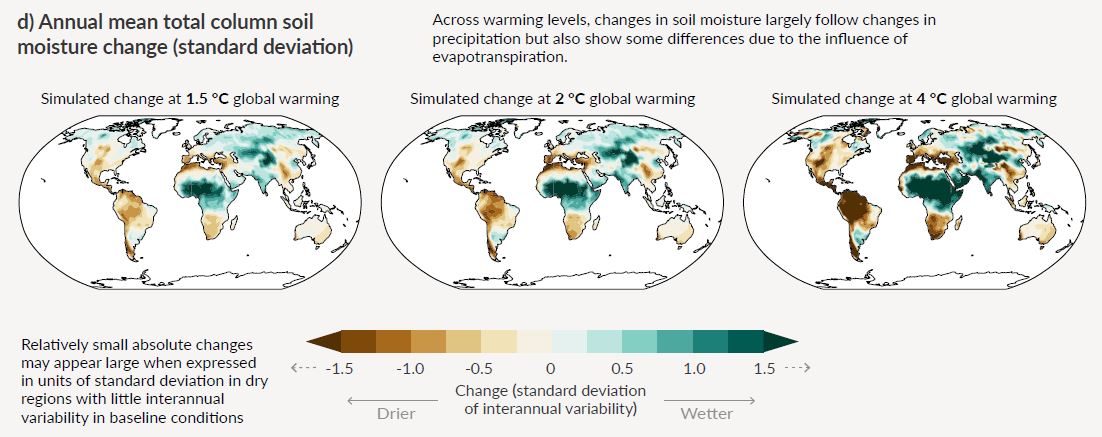

Evidence gathered since 1950 clearly shows that extreme weather events such as heatwaves, heavy precipitation, tropical cyclones, as well as droughts affecting ecological and agricultural systems, have increased both in frequency and intensity. Higher temperatures will result in more intense weather events, whether in terms of rainfall or periods of drought, as well as more pronounced seasonal differences. Without human influence, the occurrence of record temperatures, floods and wildfires would have been much less likely, the report remarks. Heatwaves like the ones recorded this summer (such as the record temperature for Europe recorded in Syracuse, Italy, at 48.8°C) used to occur every 50 years in the past, while today they occur once every 10 years. Should global warming reach 2°C, they might strike every 3 to 4 years. The less we will be able to limit global warming, the more catastrophic the consequences of extreme weather events will be.

Regional effects

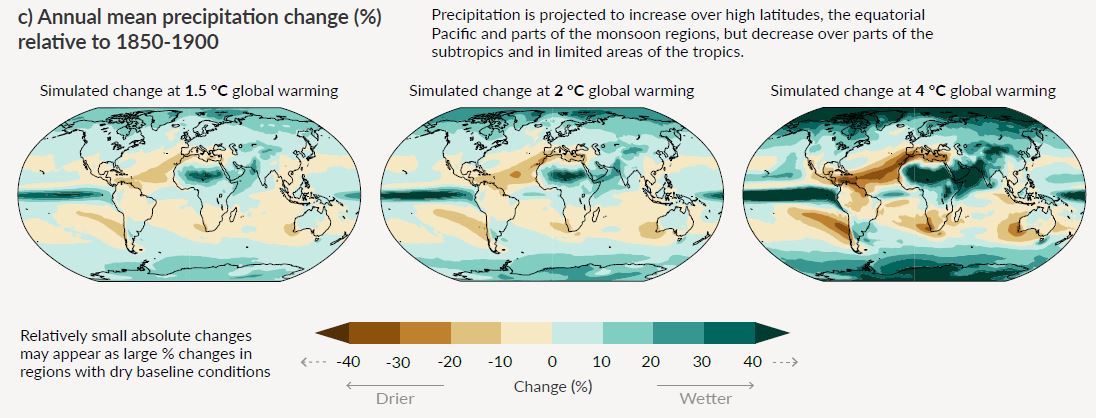

In addition to providing a global overview, the report also analyses the implications of climate change on individual areas of the planet. For example, the rise in global temperatures will alter the water cycle, leading to an increase in precipitation in high latitudes, the equatorial Pacific region, and in some monsoon areas like southern and south-eastern Asia, East Asia, and western Africa with the exception of the Sahel. On the other hand, it will cause a decrease in rainfall in some tropical and subtropical regions.

An additional factor is the gradual but steady weakening throughout the 21st century of the Atlantic Meridional Overturning Circulation (AMOC), an Atlantic current that includes the Gulf Stream, which pushes warm sea waters northward and towards the ocean surface and cold waters southwards into the depth. It is part of the thermoaline circulation (also known as the ‘global ocean conveyor belt’) and is a crucial factor in regulating the planet’s climate. The rate of its decline is difficult to ascertain. Scientists believe it will not be sudden before 2100, but if it were to accelerate (and recent observations have raised concerns among experts), regional changes would be drastic. This shift would alter climate and water cycles, tropical rainfalls would shift southwards, thus weakening African and Asian monsoons, strengthening those in the southern Hemisphere, and making Europe a drier area.

This article was translated into English by Sofia Belardinelli. The original version of this article is available here.

ALSO READ:

- IPCC: Nearly direct correlation between emissions and global warming

- IPCC: Impacts of climate change are not equal for everyone

- IPCC: The impacts of climate change on Africa

- IPCC: The impacts of climate change on Europe

- IPCC: The impact of climate change on small islands

- IPCC: The impacts of climate change on Asia

- IPCC: The impacts of climate change on Oceania

- IPCC: The impacts of climate change on Central and South America

- IPCC: The impacts of climate change on North America

- IPCC: The impacts of climate change on human settlements

- IPCC Synthesis Report: every fraction of a degree matters