It represents an "experiment" in the evolution of the cartilaginous fish after its mass extinction during the late Cretaceous period. The study was published in the journal Scientific Reports.

An international group of researchers, including Luca Giusberti from the University of Padua’s Department of Geosciences, discovered a new race of myliobatiform fossils (Lessiniabatis aenigmatica) in the Natural History Museums of Paris, Florence, and Udine. The new race of stingray has a unique and bizarre anatomy different from that of presently known species. The new body plan of the Aenigmatic Lessiniabatis, from the Eocene era, is particularly interesting because it is considered an "experiment" of cartilaginous fish during their evolution at the end of the Cretaceous period.

Stingrays (myliobatiformes) are a group of cartilaginous fishes which are known for their venomous and serrated tail stings, which the use against other predatory fish. The group include more than 360 living species each characterized by a dorso-ventrally flattened body, large pectoral fins joined at the side of the head, and a long whip-shaped tail. They live in marine and freshwater environments around the world, from shallow waters near the coast to the open sea, feeding mainly on small fish, crustaceans, molluscs, and plankton.

Fossils of the myliobatiformes breed are very abundant, but since their skeleton is mainly composed of cartilage, there is little possibility for fossilization. Their remains are mainly comprised of isolated teeth and dental plates. Only a few complete and articulated skeletons have been preserved to represent the species. The sediment remains of animal and vegetable organisms quickly deposited themselves in oxygen-free bottoms, preserving them from decomposition and other organisms, thus allowing the conservation of the smallest anatomical details. The Lessini area of Verona, near the village of Bolca, offers one of the most famous paleontological sites in the world due to the abundance and exceptional conservation of its fish. This site is the "Pesciara", whose fossils have been known to scholars since the sixteenth century, dates back to the Eocene era (about 49 million years ago). They are documented to be present in an ancient subtropical sea of coastal shallow waters associated with coral reefs. To date, over 230 species of fossil fish have been recognized and described, along with various species of crustaceans, jellyfish, molluscs, annelids, insects, and plants.

The research used in studying sharks and other breeds from Bolca are now preserved in numerous national and international museums, including the Museum of Geology and Palaeontology of the University of Padua. An international team, led by the University of Vienna, includes the University of Padua, Turin, and the University of Florida in the discovered of the new myliobatiform breed.

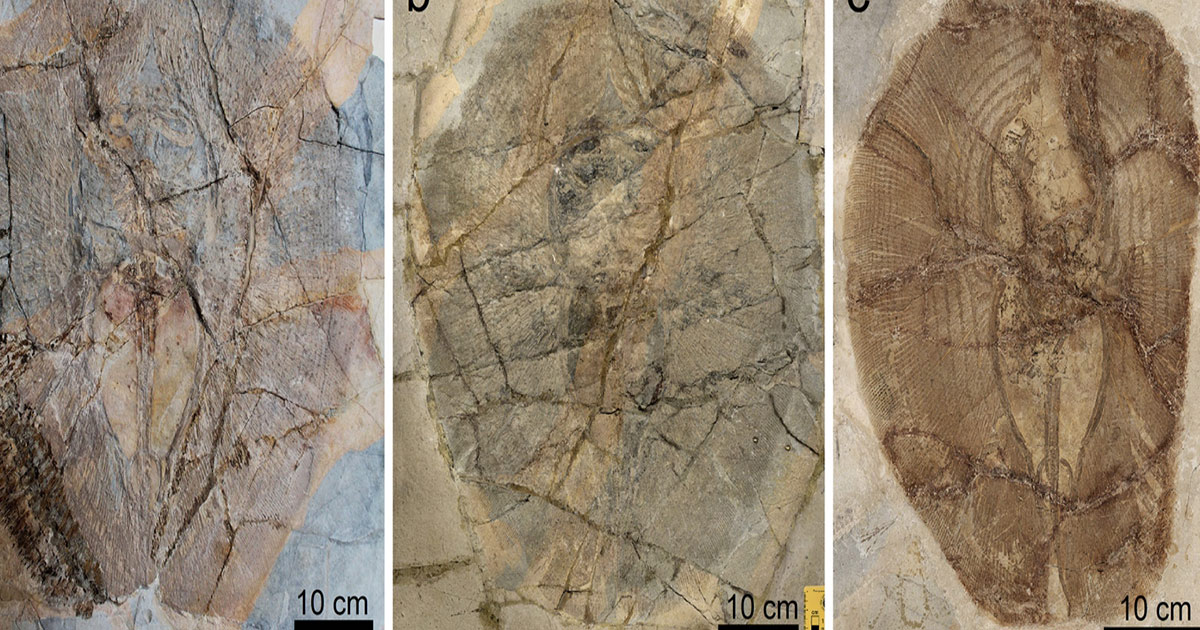

Luca Giusberti of the Department of Geosciences at the University of Padua states, "The new genus of fossil breed found in Bolca, has a peculiar anatomy unknown to the myliobatiform race. The description of the unusual breed is based on three finds, two of which I traced from the collections at the natural history museums in Udine and Florence. After its mass extinction during the late Cretaceous period, the new fossil breed represents a ‘dead-end’ to the evolution of this group of cartilaginous fish. Three fossils were found in the nineteenth century and the new research published highlights the importance of ‘excavations’ in old museum collections which can lead to surprises."

The three specimens preserved in the collections of natural history museums of Paris, Florence, and Udine, have unique and bizarre anatomies from that of currently known forms.The body is evident by the ovoid shape of the pectoral disc. The tail is small and does not protrude outside the pectoral disc while the venomous spike, typical of other myliobatiform species, is completely absent. The anatomy, or rather this bodily plane, is not known in other races. Since this species is unique and bizarre, the researchers called it Lessiniabatis aenigmatica, which means "enigmatic race of Lessinia".

About 66 million years ago, at the end of the Cretaceous period, more than 70% of the animal and plant species on Earth went into extinction. Marine environments following this event is marked by the appearance and the diversification of new species and families of bony and cartilaginous fish. The reoccupied ecological niches left empty by extinct species can be considered an experiment with new bodily and new planes of ecological strategies.

In this context, the evolution of a new body plan in an Eocene race like Lessiniabatis aenigmatica is particularly interesting because it is considered another "experiment" conducted by cartilaginous fishes during their evolution after the end of the Cretaceous period. This discovery sheds new light not only on the evolution of this group of fish but also on the recovery of the marine ecosystems after the great mass extinction 66 million years ago.